Devin Nunes, Steven Biss, and the Laptop of MAGA Secrets

Attorney Steven Biss represented famous MAGA clients in a lawfare campaign against the press. Things didn't go exactly as planned.

I. The Laptop

I learned that the lawyer at the heart of it all had some secrets of his own.

In the late summer of 2023, someone broke into the law firm of a well-known attorney in Charlottesville, Virginia, named Steven Biss. His office was allegedly “ransacked,” folders with Biss’s documents went missing, and his laptop, which contained “all” of his “client files,” was gone, “taken by an unknown person.”

Considering Biss’s client list, this was no small matter.

Biss not only represented Donald Trump’s media company, Trump Media and Technology Group (TMTG), which runs Truth Social, but also a network of MAGA luminaries who now populate the upper ranks of the Trump administration, including Kash Patel, the director of the FBI; Dan Bongino, the FBI’s deputy director; and Devin Nunes, who was the top Republican on the House Intelligence Committee and is now the CEO of TMTG and the chair of the President’s Intelligence Advisory Board.

Biss’s “client files” included a lot more than just the sensitive personal information of top Trump intelligence and law enforcement officials. In Biss’s possession were also the sensitive secrets of some of the biggest media companies in the world.

Biss is best known for suing reporters and news organizations for defamation. Several of his high-profile cases reached the discovery phase, when thousands of pages of internal documents were produced by both his MAGA plaintiffs and the media defendants they sued, including CNN, The Washington Post, NBCUniversal, and Esquire, where I previously served as Chief Political Correspondent.

Many of the documents produced during discovery in these cases were shielded from public disclosure—and even to the opposing client—by ”counsels-eyes-only” protective orders. When sensitive documents were included as exhibits or in motions, they were often redacted or filed under seal. For instance, in a lawsuit filed by the family of Michael Flynn against CNN, “highly confidential” documents were sealed at the request of Biss, and “confidential exhibits” were filed by CNN. In a Nunes case against NBC, a broad protective order covers “confidential, proprietary, or private information” exchanged in discovery, including “newsgathering information,” “competitively sensitive information,” and any personal information that if disclosed “would cause injury.” In a Nunes case against The Washington Post that touches on classified intelligence matters, the docket includes numerous sealed filings and references to “highly Confidential Material.”

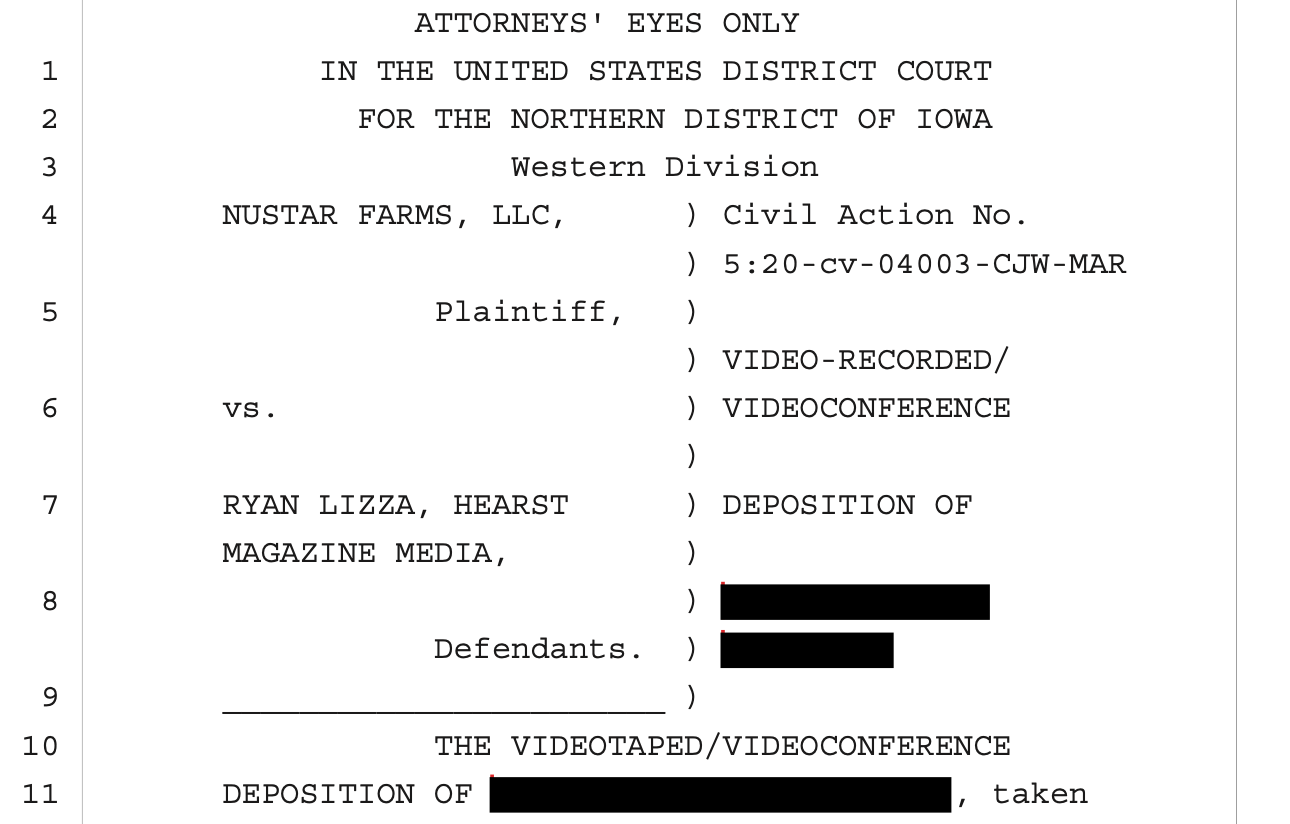

These public dockets only hint at what was in Biss’s stolen computer if it included “all client files,” because the universe of confidential material produced in discovery is much larger than what’s formally used in a case.

I know firsthand the kinds of sensitive information that parties exchange during discovery in a complicated defamation case. Nunes—Biss’s most prolific plaintiff—and Nunes’s family, filed a pair of lawsuits against me and Esquire in 2019 and 2020 over an article I wrote about the use of undocumented labor at the dairy owned by Nunes’s parents. Backed by a brilliant and dogged team of lawyers at Hearst, which owns Esquire, I spent the last six years fighting Nunes and Biss in court.

Biss’s case files in my lawsuit would include the names and personal information of undocumented workers hired by the Nunes family dairy in Sibley, Iowa, Devin Nunes’s tax returns and phone records, information we subpoenaed from Trump’s media company, files related to a political group founded by J.D. Vance, and sensitive reporting files that I turned over under the strict terms of a protective order.

Being targeted with frivolous litigation by one of the most powerful officials in America wasn’t fun. The case—and the cartoonish demand for over $100 million in damages—hung over me for years. It made it more difficult to report on Trump and his allies. It forced me to spend untold hours responding to burdensome discovery requests and preparing for two day-long depositions as well as a potential trial.

But it also gave me a much deeper understanding of the defining feature of President Trump’s first 100 days in office: the weaponization of the government on behalf of Trump and the MAGA movement against their critics.

I learned a lot tangling with Nunes and Biss, and much more when I started down the rabbit hole of what happened to Biss—and his computer—after Biss suddenly disappeared from our case in 2023. I learned what it’s like to be targeted by powerful government officials who don’t approve of what you say about them, an experience many ordinary Americans and institutions have now experienced in the last 100 days. I learned what it’s like inside the right-wing effort to turn back the clock on press freedoms. And I learned that the lawyer at the heart of it all, the one who lost that laptop with all of those MAGA and media secrets on it, had some secrets of his own.

II. Devin’s Journey

Before Trump refined and expanded this plan, Nunes and Biss were down there in the minor leagues, testing it out in courthouses across America.

When I first met Rep. Devin Gerald Nunes a decade ago, he was not who he is today. Back then, he was a defender of the old-guard Republican leadership in the House as it fought off a new wave of radical members who were making it impossible to govern. I sat down with Nunes in his office in 2015 for a long interview that focussed on his efforts to tame the fringe of his party—people he had memorably called ”lemmings” wearing “suicide vests” after they pushed a plan to shut down the government to somehow force President Barack Obama to defund Obamacare.

We got along well, and I was fascinated by Nunes’s account of a grave threat to the Republican Party that he saw growing like weeds from the party’s grassroots. He had been in Congress since 2002, and, as I reported in The New Yorker, he explained that the biggest change he’d seen was the rise of misinformation:

“I used to spend ninety per cent of my constituent response time on people who call, e-mail, or send a letter, such as, ‘I really like this bill, H.R. 123,’ and they really believe in it because they heard about it through one of the groups that they belong to, but their view was based on actual legislation,” Nunes said. “Ten per cent were about ‘Chemtrails from airplanes are poisoning me’ to every other conspiracy theory that’s out there. And that has essentially flipped on its head.” The overwhelming majority of his constituent mail is now about the far-out ideas, and only a small portion is “based on something that is mostly true.” He added, “It’s dramatically changed politics and politicians, and what they’re doing.”

Like a lot of his colleagues, Nunes seemed bewildered by these changes, which he attributed to the rise of new online outlets and outside groups spreading fake news that politicians were then obliged to address as if it were real. Donald Trump had just announced his first campaign for president in June, and yet Nunes never brought him up. At that point, Trump still had no currency in the GOP. But just months after that late 2015 interview with Nunes, Trump, the living embodiment of the conspiracy-spewing demagoguery Nunes had described, would take over Nunes's party.

Nunes’s transformation over the last decade neatly encapsulates what happened to the Republican Party. A year later, in 2016, Nunes was a member of Trump’s transition team. By 2018, his local paper in California would describe Nunes as “Trump’s stooge.” In 2021, he left Congress to work for Trump as the CEO of the company that runs Truth Social, a clearinghouse for the kind of “chemtrails-from-airplanes-are-poisoning-me” misinformation that Nunes had feared was destroying his party.

Along the way, Nunes teamed up with Biss to execute a strategy that was a precursor to what is now the signature of the second Trump administration: weaponizing the government against critics. For Nunes and Biss, that meant targeting journalists who were critical of Nunes with costly, time-consuming defamation lawsuits.

The suits were widely criticized as frivolous. But winning rarely seemed to be the point. Part of their strategy was to use the privileges afforded to litigants in court filings to smear reporters with ad hominem attacks. In one of several lawsuits against The Washington Post, Nunes and Biss described a reporter as “a puppet of the FBI and CIA” who “has a reputation in the community in which he works for being very untruthful.” (The evidence Nunes and Biss cited for the latter was a tweet from an anonymous account attacking the journalist.) Rachel Maddow, among others, was accused of “fabricating“ a story. Sometimes, the Biss and Nunes asides about their targets were just puzzling. Chris Cuomo, they alleged in one of several lawsuits against CNN, “is famous for his brash style, having recently threatened to assault a man who referred to him as ‘Fredo.’”

Starting in 2018, Nunes and Biss flooded courtrooms with lawsuits against the media. The amounts they demanded ballooned into absurd figures. Nunes sued me and Esquire for nearly $80 million in 2019. By 2023, he was suing The Washington Post for $3.78 billion for a piece that he was especially unhappy about (headline: “Trust linked to porn-friendly bank could gain a stake in Trump’s Truth Social”).

Sliming journalists under the cloak of the litigation privilege wasn’t the only purpose of the lawsuits. In this new world that Biss and Nunes helped usher in, and that the Trump administration is now perfecting, attacking reporters personally is designed to manufacture a conflict of interest that silences the reporter. I’ll never forget the first time this happened to me. I was appearing on CNN, and the conversation turned to Nunes. The host paused to inform viewers that, in the interest of full disclosure, she needed to mention that Nunes was suing me. That, of course, is exactly what powerful officials want to achieve with lawsuits and other attacks on reporters—to put an asterisk on their coverage by creating phony conflicts.

Nearly all of Nunes and Biss’s defamation cases got thrown out. I’m not aware of any that have gone to trial or resulted in awards, and I’m only aware of one, against NBC, that is still alive. By that standard, they were failures. But if the point was to harass reporters, drag them into conflicts that make it difficult to cover Nunes, Truth Social, or other Biss clients, obtain confidential information through discovery, and saddle news organizations with expenses that encourage them to be more risk averse, then the Nunes-Biss lawfare has arguably been quite successful. And influential.

Trump has taken this all to the next level with his own media lawsuits, his executive orders targeting individuals and law firms, his barrage of social media posts attacking reporters and critics, and the gradual transformation of the executive branch into a personal tool that he can leverage against his long list of enemies.

Before Trump refined and expanded this plan, Nunes and Biss were down there in the minor leagues, testing it out in courthouses across America.

III. Taking the Fifth

As Nunes and Biss’s sensationalistic lawsuits on behalf of famous MAGA clients gained notoriety on the right, business from small-time plaintiffs started booming.

Steven Scott Biss was one of the strangest and most unpleasant people I have ever encountered in my life. He’s from Canada but became a hardcore America Firster and Trump devotee. He seemed to spend most mornings posting links to Breitbart and The Federalist on Truth Social. There were rumors that his lawsuits were funded by mysterious right-wing benefactors. But he seemed to have little assistance with his filings, appeared to be constantly overwhelmed with the number of cases he had going, and often overlooked or abandoned potentially promising avenues of strategy in his big cases.

Biss had a checkered past as a lawyer. There were numerous complaints against him filed with the Virginia State Bar. He was officially reprimanded for violating the state’s conflict of interest rules in 2010. In a brief, CNN once summarized Biss’s history of unethical and unprofessional behavior. Biss had “been suspended twice from the Virginia Bar, once for fraud, and once for ‘conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit, or misrepresentation’ by holding himself out as an attorney while his license was suspended.” When sanctioning Biss for his “bad faith conduct,” a federal court in Maryland noted that it was joining a “chorus” of courts reprimanding Biss. Another court admonished Biss for his “ad hominem attacks” which “the court cannot tolerate” and noted that his conduct “falls well below the standards of practice this Court expects.”

Biss’s partnership with Nunes turned things around for him. It wasn’t just Patel and Bongino and the Flynn family and Trump’s media company that sought his services. As Nunes and Biss’s sensationalistic lawsuits on behalf of famous MAGA clients gained notoriety on the right, business from small-time plaintiffs started booming.

Michelle Di Blasi, from Henrico, Virginia, retained Biss to represent her in a legal malpractice case and paid him $10,000 in December 2022.

Dr. Jennifer Anne Shaw, from Manassas, Virginia, wired Biss $20,000 in April 20023.

Gregory Walker, from Beaverdam, Virginia, paid Biss $12,000 in July 2023 to represent him in a foreclosure case.

Biss also started to attract clients far from Charlottesville. Peter A. McCullough, a Dallas doctor, asked Biss to file twelve defamation suits for him, including against Rolling Stone and Gannett. Biss told him he conducted a “review of numerous hit pieces on the Internet and social media” and that the doctor’s cases were “very strong.” McCullough wired Biss $20,000 in April 2022.

Michael Kenny, from Cynthiana, Kentucky, gave Biss $10,000 in May 2023 to help him with a defamation suit.

Other clients entrusted Biss with large sums of money to hold in escrow without asking too many questions. Christopher Alburger, from Manakin Sabot, Virginia, gave Biss $123,795.00 to place in an escrow account—Biss’s idea—while the client awaited the outcome of a complaint against his employer.

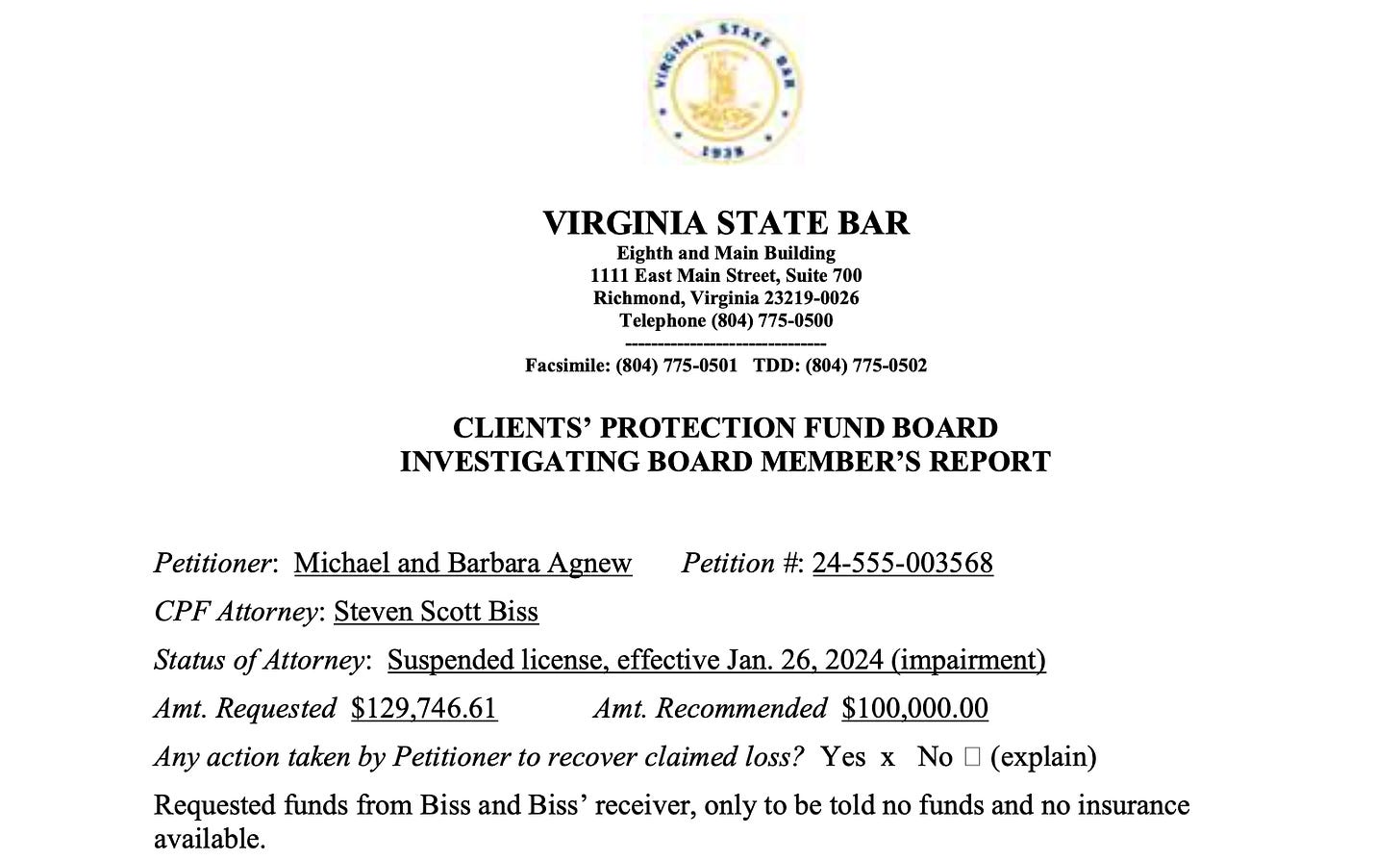

Mike and Barbara Agnew, longtime Biss clients, gave Biss $129,746.61 to keep safe while the couple waited for a deal to be completed.

It seemed unbelievable that he was able to juggle all of these cases.

Biss was zealously devoted to his high-profile cases, especially his suit against me. I couldn’t understand why he was pursuing it. In 2020, a judge in Iowa threw out Nunes’s original lawsuit on a motion to dismiss, the point in civil litigation before discovery has really started. But Nunes’s father and brother, who operated the family’s Iowa dairy, NuStar, also sued. The judge tossed out most of their claims, but he allowed discovery to proceed on a single question: Did the Nunes family and NuStar knowingly hire undocumented workers?

I thought for sure that the case would be withdrawn. Why would Biss and Nunes want to subject the Nunes family to an intrusive process that would force them to turn over their company’s most sensitive internal files and potentially expose them to accusations of criminal wrongdoing? The Nunes family admitted that they weren’t paying anything to Biss, and they sometimes seemed oddly detached from the case. I always wondered whether the Nunes family really understood what Biss and Devin were getting them into and what litigation might reveal.

The turning point in the case came in May 2021, when we deposed the first NuStar employee in Iowa. Nathaniel Boyer, an enormously gifted attorney for Hearst, was prepared with a stack of documents. Boyer spent more time than anyone else on the legal team interacting with Biss, and his patience and professionalism in the face of Biss’s antics were impressive.

Boyer began by asking the dairy worker, whose name I am witholding, some basics about his path to the U.S. The employee described a bus trip from Mexico to the United States through Nogales, Arizona, to work in construction in his early twenties. Boyer asked about his immigration status.

“Are you a permanent resident of the United States right now?”

“Yes.”

Biss was quiet, which meant he was happy about how things were going. When his witnesses got into trouble during depositions, Biss would interrupt and complain and bully opposing counsel. But this employee was validating the Nunes family’s claim that he was legally authorized to work in the U.S.

But then Biss started to get agitated.

Boyer presented the witness with a copy of a traffic ticket.

“This is harassment!” Biss said. “Who cares if the guy was cited for a traffic offense?” It was irrelevant!

“It's clearly relevant for various reasons that it's striking to me that you haven't realized,” Boyer said.

He presented another document.

“This is your signature on this document, Defendants' Exhibit 5; right?”

“Yes.“

Biss interrupted again. “If it keeps going on like this,” he warned, ”I am going to cancel the deposition.”

Boyer showed the witness his I-9 form, the federal document that both an employee and employer sign, attesting, “under penalty of perjury,” to the employee’s identity and authorization to work in the United States.

Biss interrupted and demanded that the entire transcript of the deposition be designated as confidential. (It was later unsealed with minor redactions.)

Boyer asked the witness to look over the I-9. “I just want to walk through this document,” he said.

On the form, the employee, who had just said he was a permanent resident, swore that he was a “citizen of the United States.”

The employee’s lawyer, Justin Allen, who had been silent throughout the proceeding, now realized his client was in serious trouble and asked for a break.

“I’ve advised my client,“ Allen said when they returned 15 minutes later, “to invoke his Fifth Amendment right regarding questions about this document.”

Biss lost his shit. He had to have known the case was probably over. He stopped the deposition for two hours. When everyone reassembled, the witness had inexplicably fired his lawyer, and the deposition was canceled.

The following morning, the lawyers assembled in front of the magistrate judge in the case for a virtual hearing. He was appalled. What had happened, he said, was “very troubling” and “deeply concerning.”

Biss had no defense other than to sputter. “There are I-9s and green cards and Social Security cards and driver's licenses for everybody,” he insisted. “This is a stunt, Your Honor. This is not real.”

This is not real. I remember being dumbstruck by that line when I first read it in the transcript. Biss seemed to me to live in a kind of social media bubble where it was common to simply deny reality in the familiar way for which Trump is known. It was exactly the kind of information ecosystem that Nunes, back in 2015, had warned me was taking over the GOP.

Biss assured the judge, without any evidence, that the workers “don't want to invoke their Fifth Amendment.”

The lawsuit had put Hearst in the uncomfortable position of having to prove that the NuStar dairy workers were not documented. When it became clear that we couldn’t rely on Biss or the Nunes family to obtain adequate legal representation for the employees, we successfully petitioned the court to appoint counsel for them.

By mid-August of 2021, Hearst’s lawyers had finished the depositions of six employees. All six employees pleaded the Fifth to almost every question they were asked.

IV. Never Tweet

Our case was being set up by the right as a vehicle to overthrow the most important First Amendment free press case in American constitutional history.

A rational person might have withdrawn the lawsuit at that point. This was clearly going to end in embarrassment for the dairy. But the case suddenly got new life.

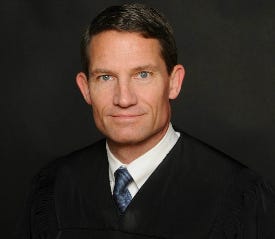

Devin, whose lawsuit had been thrown out, appealed the decision, and a three-judge panel for the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals revived one of his claims in the most bizarre opinion on defamation law in many years.

Judge Steven Colloton, who wrote the opinion, agreed that all of the congressman’s claims with respect to the original article were meritless. But, he said, a tweet linking to the article that I had sent in 2019, after Nunes filed his lawsuit, might be defamatory.

The chain of logic that Colloton used to reach this conclusion required multiple contortions.

First, contrary to every other jurisdiction in America, Colloton said that posting a link to an article can be considered republishing the entire article. Second, he said that being sued over an article, no matter how spurious the lawsuit—and Nunes’s original complaint was filled with so many garbage accusations that the lower court later struck many of them from the record—could be interpreted as putting a journalist on notice that claims in the article were false and therefore make previously non-defamatory statements suddenly defamatory.

On top of all that, the claim that was revived was not regular old defamation, but a mutant category of defamation law known as “defamation by implication.” I am clearly biased, but the case made me a zealot in opposition to defamation by implication.

To give you a sense of how vague and subjective implied defamation can be, just look at how the two different courts viewed the same article.

The lower court judge concluded, “no reasonable reader could read the Article to imply [Devin Nunes] conspired with others to hide NuStar’s use of undocumented labor.”

Colloton read the same article and confidently proclaimed, “a reasonable reader could draw the implication that Representative Nunes conspired to hide the farm’s use of undocumented labor.”

As a writer, I would prefer to have judges who are required to stick to what I actually wrote rather than trying to divine what a reader might imply.

The Colloton decision was shocking to many First Amendment lawyers. For me, it was an eye-opening experience in how activist judges can operate. It was alarming to be targeted by the top Intelligence official in Congress. But at the end of the day, I knew Nunes, whom I had covered for years, was an extreme partisan who saw all of public life as political mortal combat, and I had no expectation that he operated in good faith. But I had never seen up close, in a case where I knew all the facts, how a federal appeals court could twist itself into knots to arrive at what seemed to me a politically-motivated decision.

At the district court level, we had a judge, C.J. Williams, who, although he was appointed by Trump, did not exhibit a hint of ideological bias. He was the definition of a workmanlike judge who applied facts and law to the case and crafted sober opinions free of any rhetorical flourishes. When I disagreed with one of his decisions, it was never because it looked like he was trying to manufacture a preconceived outcome.

My view of the Eighth Circuit was different.

The opinion by Colloton, who was on Trump’s 2016 list of potential Supreme Court nominees, seemed so at odds with settled law that I suspected there had to be some broader agenda that was being pursued.

I asked a lawyer friend to review the case and provide a confidential memorandum about it.

He reported back with a 2000-word analysis that was revealing. He agreed with us on the law, noting that a recent case out of the D.C. Circuit that the Supreme Court had declined to review, Tah v. Global Witness Publishing, found “‘no support in our First Amendment case law’ for proposition that publisher must ’credit’ a defamation plaintiff’s ‘denials.’” Tah v. Global Witness was well known to media lawyers because Judge Larry Silberman wrote what was described as a “preposterous and preposterously silly dissent,” calling upon the Supreme Court to overturn Times v. Sullivan, the cornerstone case protecting press freedoms.

All of this was directly connected to Colloton’s curious decision, according to my friend:

[I]f you are wondering why the Eighth Circuit reached in the way that it did to reach the result that it did, wonder no longer. ... [Judge Colloton] clerked for Larry Silberman, before clerking for Chief Justice Rehnquist … Colloton would have done anything he could in your case to endear himself to Silberman on New York Times v. Sullivan because Silberman has urged the reversal of that landmark First Amendment opinion as his final mission in life.

And if you already know this, don’t forget this interesting sequence of events. Tah, the D.C. Circuit decision in which Judge Silberman (Colloton’s judge) dissented was decided March 19, 2021. … Your case was submitted to the Eighth Circuit on April 14, 2021. … It was no accident that Judge Colloton cited to Silberman’s dissent in Tah in his opinion for the court in your case. Nor is there any question he would have wanted somehow to bring you within the reach of New York Times v. Sullivan’s ‘actual malice’ exception to endear himself to Silberman.

In other words, according to my friend, who knew all of these players intimately, our case was being set up by the right as a vehicle to overthrow the most important First Amendment free press case in American constitutional history.

V. Substantially, Objectively True

“NuStar employed undocumented aliens, and did so knowingly, prior to the Esquire article being published on September 30, 2018. NuStar continues to employ some of those employees today knowing that they are not documented.” — Former ICE special agent Claude Arnold

What Colloton didn’t know, if indeed he had his eye on killing Sullivan, was just how bad our case would be for that cause. Back in Iowa, we got just about everything we wanted out of discovery: the results of an I-9 audit that NuStar had conducted after my article appeared, an order directing the Social Security Administration to provide us with information about every NuStar employee since 2006, and even some limited information about who might be funding the case.

We had an ex-ICE special agent, Claude Arnold, who was formerly the chief of ICE's Transnational Gang unit at ICE Headquarters in Washington, DC, review the massive record we had assembled. He produced a devastating expert report that was not made public but has subsequently been unsealed.

“Based on my years of experience,” he wrote, “which includes being involved in dozens of prosecutions of employers for the hiring and harboring of illegal aliens, I can say with confidence that NuStar and its officers and owners engaged in conduct that could subject them to civil fines and criminal prosecution for knowingly hiring, continuing to employ and/or harboring an illegal alien.”

When I first read the concluding paragraph of his report, all I could think about was why in the world Nunes and Biss had subjected Nunes’s family to any of this?

Our expert wrote:

From the company's inception, NuStar did not comply in good faith with the employment eligibility verification laws and regulations of the United States and exhibited a pattern and practice of not properly completing forms I-9. This began with NuStar's very first employee of record [NAME REDACTED], who was hired on December 4, 2006, after he presented counterfeit resident alien and Social Security cards and continues today with NuStar knowingly employing current employees with expired work authorization documents. NuStar employed undocumented aliens, and did so knowingly, prior to the Esquire article being published on September 30, 2018. NuStar continues to employ some of those employees today knowing that they are not documented.

In April 2023, Judge Williams, who was previously a lead prosecutor on one of the largest immigration enforcement cases in U.S. history, wrote a 101-page opinion that was a complete victory for me and Hearst over Nunes and NuStar. The Williams decision was meticulous, apolitical, and fact-based—the opposite of everything that is now a plague on public life in the Trump era.

The money quote came in Williams’s conclusion to his careful dissection of the mountain of evidence we produced about the dairy’s labor practices:

The assertion that NuStar knowingly used undocumented labor is substantially, objectively true.

I felt sorry for Devin’s parents, Devin’s brother, and their workers. It was one thing to be thrust into the national spotlight by a reporter pointing out the well-known fact that dairies tend to run on undocumented labor.

It was quite another to publicly subject your business to an audit by a former ICE agent, who credibly described it as a criminal enterprise, and then have a federal judge point to those findings—“it is alleged plaintiffs have engaged in repeat violations of laws regulating employment of undocumented laborers, which can result in imprisonment”—and conclude that it was substantially true all because your son/brother and his ethically challenged lawyer assured you that there was an eight- or nine-figure windfall at the end of it all that would make all the pain and public scrutiny worth it.

There was little downside for Devin. By 2022, according to his employment agreement, he was making a million dollars a year, in addition to a $7,000 per month housing allowance and annual bonus. Moreover, he’s used to the combat of public life. Indeed, far from having his reputation damaged, Trump awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom and made him a high-paid CEO at a company currently valued at over five billion dollars.

Devin’s family members in Iowa, on the other hand, disclosed modest incomes (his brother said he made $62,500 in 2020) from the backbreaking work of running a dairy, and they had their business and their lives turned upside down by Devin’s crusade to weaponize the courts and the discovery process against critics in the press.

Why did Devin Nunes allow his family to go through this? My best guess is that he was blinded by what he thought of as a higher calling to overturn Sullivan. That larger project might explain why Nunes pursued the litigation so persistently for so long despite the embarrassment it inflicted on his mother, father, and brother, who admitted in their depositions that they weren’t paying for anything, weren’t very involved with the details of their own case, and that it was Devin who connected them with Biss.

But it could also be that he just isn’t very smart and genuinely believed that his parents and brother ran the only dairy in the Midwest that didn’t hire undocumented workers.

Despite our victory, the case wasn’t over. Biss immediately started working on a new appeal to the Eighth Circuit.

It nearly killed him.

VI. Dodecahedron

On the morning of August 16, 2023, Biss started his day the way he usually did, scanning right-wing news sites and posting on Truth Social. He had a signature formula in which he would write a pithy all-caps headline above a short summary of the article. He started at 6:25 AM with “YOU’RE NEXT” about a Daily Caller article summarizing a Josh Hawley appearance on Fox News. He posted a few items about Trump’s legal cases. “These are deeply corrupt Democrats acting in concert to harm one man,” he noted about the Georgia indictment. “Truth by any means is the only path to victory.” He finished up at 7:48 AM with the last of several posts about trans issues. “Muslim transgender wants balls back,” he wrote.

It was the last thing Biss ever wrote on Truth Social.

Minutes after the testicles post, Biss turned his attention to his lawsuit against me and started working on a filing for the appeal to the Eighth Circuit, his life raft in the case.

Though few knew it at the time, Biss was apparently under an enormous amount of pressure in both his personal and professional life. According to court documents that have never previously been made public, Biss had separated from his wife, Tanya Cornwell, and moved out of their rural Virginia home in 2021 and into an apartment in Charlottesville. Their relationship had badly frayed. In a court filing, Cornwell alleged her husband had a “bastard child” that he had “paid a lot of money to keep” “secret.” Other filings included private emails in which she complained about her husband’s “dodechahedron [sic] of whores”—a dodecahedron is a 12-sided object—and said she felt like a hostage to a person she wanted to divorce.

Things were similarly fraught at work for Biss. On August 14, the Agnews, Biss’s longtime clients who had given him the $130,000 to place in escrow, sent Biss an urgent request. “The sale is closed,” Mike Agnew wrote to Biss, “so at this point it is rightfully ours.” He asked Biss to “overnight us a check for the entire 130k.”

Agnew’s message would have been a particularly alarming and stressful email for Biss to receive, because, in fact, Biss didn’t have the client’s money anymore. Biss didn’t write back.

Biss had been ignoring emails and phone calls from bewildered clients for months. By mid-August, Gregory Walker, Michelle Di Blasi, Dr. Jennifer Anne Shaw, Peter McCullough, Michael Kenny, and Christopher Alburger were all demanding to know where their money was or why Biss was ghosting them.

As Biss’s marriage dissolved and his list of angry clients grew, he was also juggling a host of complex issues in several high-profile defamation cases, including Nunes’s lawsuit against NBC and Trump Media & Technology Group’s lawsuit against The Washington Post.

But on that morning of August 16, Biss turned his attention to his white whale, the two lawsuits for some $100 million against me and Esquire that would be heard by the appeals court the following month.

The Eighth Circuit is a stickler for rules, and Biss was struggling to follow them. Since mid-July, he had already twice asked the court to extend the deadline for filing all the relevant material for the appeal, and now he was bogged down with the logistics required to submit thousands of pages of records in the case.

At 8:27 AM, on August 16th, after he finished up on Truth Social, Biss filed another motion asking the court for more time to submit a corrected brief. As far as I could tell from a review of the dockets in his active cases, it was the last legal filing Steven Biss ever made.

Sometime later that day, Biss suffered a massive stroke.

He was taken to the intensive care unit of the University of Virginia Hospital. The stroke caused “severe physical and cognitive impairment,” according to a medical report obtained by Telos News. Biss couldn’t talk, and he couldn’t walk.

And that’s when things got really weird.

VII. The Conservator

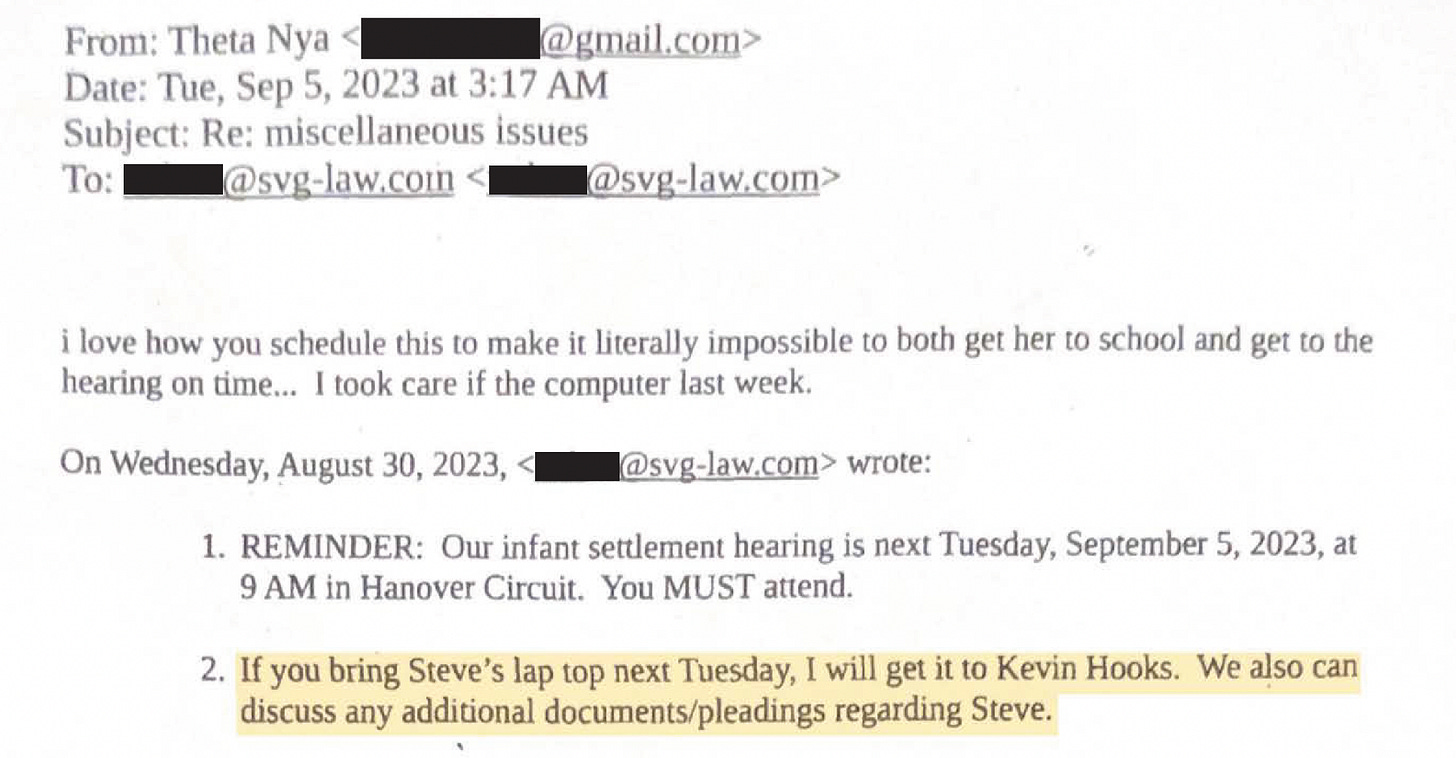

On August 30, two weeks after Biss’s stroke, a Virginia lawyer named Harvey J. Volzer sent an email to Biss’s estranged wife, Tanya Cornwell.

“If you bring Steve's lap top next Tuesday, I will get it to Kevin Hooks,” he said. “We also can discuss any additional documents/pleadings regarding Steve.”

Kevin Hooks is a prominent private investigator in Virginia whose firm, Interprobe, offers, among other things, “device data extraction” services.

Cornwell responded early in the morning on September 5: “I took care if [sic] the computer last week.”

Biss was said to be completely “incapacitated,” and he was transferred to The Laurels, a long-term care facility in Charlottesville. According to court documents, Biss was unable to handle his own finances or play any role in his ongoing cases and was “not expected to be able to return to the practice of law.”

However, several weeks elapsed before any of this news about Biss trickled out to the defendants in Biss’s multiple lawsuits or to the Virginia State Bar (VSB), which can ask the courts to place the law firm of an incapacitated attorney into receivership. The VSB, which started to get complaints from Biss’s clients, said that it didn’t learn about Biss’s condition until September 6. It wasn’t until September 20 that the VSB received permission from a court in Charlottesville to take over Biss’s law firm.

Biss’s replacement in my case was Jesse Binnall, a lawyer for Trump and the Trump campaign who is also known for his work on cases related to the 2020 election and January 6. Binnall officially replaced Biss on September 11, weeks after the stroke. On September 25, Binnall reported that he still couldn’t locate any of Biss’s files from the case and that Biss “is not currently able to communicate with anyone.” (Binnall argued, without any evidence, that Biss was likely medically impaired while writing the appellate brief in our case before his stroke and that Binnall should therefore be allowed to write a new one. We opposed this, and the court ruled in our favor.)

On November 13, almost three months after the stroke, Binnall still couldn’t get Biss’s files, and he gave the court a dramatic update:

After Mr. Biss’ emergency, but before the appointment of the receiver, Mr. Biss’ office was broken into and ransacked by an unknown individual. Mr. Biss’ files are now no longer in order. Further, Mr. Biss’ laptop, with all client files, is also missing.

During this period, some unusual things were happening between Volzer and Cornwell.

An email on August 24, just eight days after Biss’s stroke, suggests that Volzer had been urgently trying to contact Cornwell. She seemed to be angry that he wouldn’t stop calling her and accused him of ignoring her calls for a year when she needed him to help her get a divorce. His indifference, she said, had “made steve's kidnap plan work perfectly.”

By early October, Cornwell and Volzer seemed to be aligned in a plan to have Volzer take over Biss’s assets.

“I, Tanya Cornwell, am the wife of Steven Biss, who is impaired due to a massive stroke,” she wrote to Volzer in an email on October 2. “I consent to the appointment of Harvey J. Volzer, an attorney in Alexandria, VA, as conservator of my husband's finances.”

A few days later, Volzer went to the same court in Charlottesville that placed Biss’s law firm in a receivership and asked to be appointed as Biss’s conservator.

According to Volzer, Biss was not expected to ever practice law again, and he needed to support his wife, son, minor daughter, and a child Biss fathered “by a woman not his wife” whose address was unknown. Volzer told the court that his petition was supported by Cornwell and that the court should allow him to “take control of all real and personal property of Biss,” pay his bills, and support his family. He submitted a draft order for the judge, who signed it a few days later.

The State of Virginia now controlled Biss’s law firm, and Volzer now controlled all of Biss’s property, bank accounts, and finances. If there was some secret financier funnelling money to Biss to finance Nunes’s lawfare, as many Biss defandants always suspected, Volzer said he didn’t find it. In fact, he didn’t find anything. Volzer said that Biss was completely broke.

“There is no money to pay any creditor, household expense, former client, etc.,” he wrote to the court. According to an email from one of Biss’s banks, M&T, Biss’s personal account was closed on September 19, and his business account was closed on October 4. Biss had two checking accounts at Atlantic Union Bank, which said one of Biss’s accounts had a $10 balance and hadn’t been used since 2021, and that the other had a balance of $33.36.

Biss’s recovery was painfully slow and it was made more difficult by this dire financial situation. At one point, Biss was threatened with eviction from his medical facility for unpaid bills, and his guardian was desperately trying to get assistance to enroll him in Medicaid. Volzer later reported that Biss’s house was facing foreclosure.

Whatever relationship Volzer and Cornwell previously had, it rapidly deteriorated after Volzer was placed in charge of Biss’s assets.

“Tanya, PLEASE give me the bills you took from Steve’s office so I can consider/pay them,” Volzer wrote to her on December 15. “I cannot help persons who do not help themselves.”

Cornwell responded with extraordinary accusations.

She said that Volzer “lied to the court,“ was “stealing” her assets, and that Biss was, in fact, “not incapable of making his own decisions.”

In the email to Volzer in which she lists the names of women she apparently believed were part of her husband’s dodecahedron, Cornwell named a Virginia attorney and alleged that she had access to one of Biss’s online accounts. “[T]his bitch is the one using his email,” she wrote.

Volzer told me he had no way to know if it was true or not.

Cornwell’s paranoia about Biss also started to surface, according to court documents. “[I]t makes me completely uncomfortable that u seem to know all the same CIA stooges a[s] steve,” she wrote to Volzer.

Cornwell allegedly started to spread fantastical conspiracy theories about Biss. According to Jim Greer, an Ohio man who says Biss screwed him out of $20,000, Cornwell sent Greer an unusual text message in January.

“It is her belief,” Greer wrote to the court, “that Mr. Biss became compromised, after more than 80 complaints to the Virgina [sic] Bar, and then began to cooperate with the opposition lawyers in key cases, such as Michael Flynn and Robert Malone, who were his clients as plaintiffs.”

I called Greer, but he declined to talk to me. “Go fuck yourself,” he said and hung up the phone.

The feud between Cornwell and Volzer descended further into chaotic and acrimonious exchanges of charges and countercharges in which Biss, who could not defend himself, became a casualty.

In February, Cornwell wrote another message to Volzer complaining about his management as conservator and comparing him unfavorably to her husband. “This is the thing I spent 25 years begging my owner for my own money,” she wrote, “the fuck im begging a thief who stole all my money for my money yu need to go to jail.”

She returned to the judge who had appointed Volzer and asked to have Volzer removed as conservator.

“Mr. Volzer has perpetrated a fraud upon the court by stating I endorsed him to act as conservator for my husband of 25 years, Steven Biss,” she wrote. “I did not.” She accused Volzer of having a conflict of interest because he represented her against Biss in a recent personal injury lawsuit. She also claimed Biss was making progress and “regaining his ability to speak.” She attacked Volzer for revealing Biss’s “bastard child.” She said Volzer had bribed her son by setting him up in Biss’s $2000 per month Charlottesville apartment, and she accused Volzer of stealing her assets and using the conservatorship to control her, allegedly telling her, “I own you.”

“[D]espite the rumors told to the court,” she wrote, “I have no mental defects.”

Volzer responded two weeks later, denying all of Cornwell’s accusations. He produced the email from Cornwell to him supporting his role as conservator. She responded that the email actually had a different purpose: “He went behind my back to do this [the conservatorship] with an email he swore would only be used for the banks.”

In March, there was a hearing on Volzer’s conservatorship, and it did not go smoothly. The court ordered sheriff’s deputies to detain Cornwell because of what the judge called her “misbehavior.” She was cited for contempt of court and sentenced to two days in jail.

To defend himself from this flurry of personal attacks from Biss’s wife, Volzer produced a batch of emails between himself and Cornwell that he said put “her mental competence in question,” including a December email in which Cornwell accused her husband of somehow being involved in a murder.

VIII. Chain of Custody

The subject line got right to the point: “MURDER COVER UP.”

On December 7, Cornwell sent an email to Volzer, the conservator; Elliott P. Park, Biss’s receiver; and Tenley Carroll Seli, the official handling Biss’s case at the Virginia State Bar.

“So anybody want to explain where Steve got 3 million dollars after Jim Dimartino's death when he was suspended the entire prior year?” she wrote. “OH YEAH that would the 506 exception that they used to divvy up companies they stole using the SEC. So iam going to get steve's tax returns today from where I store my stuff to demonstrate that at no time did steve ever make this kind of money. So enjoy the notoriety. You are covering up murder, there is an innocent man in jail.”

Cornwell seemed to be referring to the death of a Long Island lawyer who was murdered in 2008 in a $10,000 contract killing. DiMartino’s business partner, Ronald Thornton, was convicted of conspiring with an exotic dancer he knew from a local strip bar, Shady Al’s. The stripper helped recruit a friend who executed DiMartino outside a diner in Commack, coincidentally a few miles from where I grew up. Thornton is serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole.

When I asked Volzer about this, he brushed it off. “She made so many outrageous allegations,” he said. “I tried to find Steve Biss’s alleged girlfriends and murder victims and all this other stuff and couldn't find them. Where did she come up with that? Out of whole cloth as far as I'm concerned.”

Buried in the conservatorship court documents obtained by Telos News are a series of emails that Cornwell apparently submitted that appear to be exchanges between Biss and a Jim DiMartino in August and September 2008. In that correspondence, Biss demands to know why he hasn’t received a payment that he’s been waiting on for weeks. Biss seems to accuse DiMartino of defrauding him. The DiMartino in the emails seems to ignore Biss until Biss threatens legal action, which prompts DiMartino to respond with a long, angry email that includes a lot of all caps. The Jim DiMartino who was a lawyer killed in New York was murdered the following month, in October 2008. At his trial, it came out that he and the business partner who had him killed were involved in some shady financial shenanigans.

Are the emails fake? Was there some other lawyer named Jim DiMartino who was killed that year that Cornwell is referencing? And why was Cornwell accusing her husband of being involved in a murder?

Cornwell, Biss’s guardian, Biss’s receiver, and the Virginia State Bar’s Seli did not respond to my interview requests. Someone claiming to be “The Tanya” did reach out to me on X. “You in DC?” they wrote. “I have the emeneneffin motherload = if you pull the right lawyer's tail the whole shitchilada screams.” This certainly sounded like the same person who coined the phrase “dodecahedron of whores,” but there was no way to tell and they didn’t respond to my subsequent message.

Volzer was the only one who would discuss the case, and he thought Cornwell’s accusation was an absurd lie.

However, Cornwell actually got the last word in court. In June, the judge granted her petition to remove Volzer as conservator. In fact, the court essentially ruled, she wasn’t so crazy after all.

Cornwell’s battle with court-appointed officials who now control Biss’s life has continued in a separate case in the same Charlottesville courthouse, but all of the documents and proceedings in that case, which was active as recently as March 31, are now sealed.

By all accounts, it was Cornwell who took Biss’s laptop. Volzer told me that they were planning on bringing it to the private investigator to “see what was on the computer” but that “he never got the computer.”

“Why’s that?” I asked.

“Ask Tanya,” he said in the way someone does when they want to suggest there’s a lot more to the story. He said the computer was in Biss’s office and that Tanya “took a bunch of files and the computer back home.”

He added, “What happened after that is anybody's guess.”

In July, the judge in Charlottesville tried to determine what happened to Biss’s computer, but his account makes things even murkier. Cornwell, the judge wrote, “retrieved [Biss’s] desktop computer from his office and turned it over to this Court.” (The mention of “desktop computer” suggested to me that he might not even be talking about the infamous laptop, but maybe that’s reading too much into his wording.) He wrote that the court “sent the computer to the Virginia State Bar (VSB) in Richmond,” but he doesn’t say when.

He also said that the “computer Ms. Cornwell took from [Biss’s] office after his stroke is in the possession of the VSB and/or Elliot Park,” Biss’s receiver, who didn’t respond to me.

Volzer weighed in with his own account of what happened after Biss’s stroke, adding some additional mysteries about Steve’s files and the laptop’s chain of custody. Volzer said Biss’s son also removed files from Biss’s office and put them in storage.

“Ms. Cornwell removed files and a computer from her husband's office,” he added. “Whether any other computers, phones, or other storage devices were taken is unknown. Whether files were lost, destroyed, deleted, or withheld is unknown. Ms. Cornwell did return some items pursuant to this Court's order.”

As for Volzer, “This conservator has no client files.”

IX. Zero Services Rendered

The Virginia State Bar stripped Biss of his law license due to “impairment” in January 2024 and has been hearing from a steady stream of Biss’s clients who say he defrauded them.

Walker, the foreclosure case client from Beaverdam, Virginia, said that Biss “avoided” him after he took his $12,000, and that Biss did no work on the case.

Di Blasi, from Henrico, Virginia, proved that Biss had taken her ten grand and “did nothing for me.” Once, when she managed to get Biss on the phone to complain, he told her to stop calling her.

Dr. Shaw, from Manassas, Virginia, who had wired Biss $20,000, said she could only get hold of him once more after he got her money. Biss said he was writing a demand letter for her, but she had “no evidence any work was done.”

As for Dr. McCullough, from Dallas, who had given Biss $20,000, Biss did file one of the twelve lawsuits he promised, and he even sent McCullough the complaint. What he didn’t tell McCullough was that the two defendants in the case were never served and that the case was dismissed. Biss apparently prepared a second lawsuit for McCullough, but he never filed it, and he stopped responding to his messages.

Kenny, from Cynthiana, Kentucky, who gave Biss $10,000 to file a defamation suit, said Biss never even sent him a retainer agreement, and there’s no evidence Biss ever did any legal work for him. “Zero services rendered,” Kenny reported.

Alburger, from Manakin Sabot, Virginia, who had trusted Biss with $123,795.00 to hold in escrow, tried to recover the money. Like the Agnews, who lost their $130,000, Alburger learned that the escrow funds “were used for some other, unauthorized purpose and are now gone.” The State of Virginia declared Biss guilty of “dishonest conduct” and, through its Clients’ Protection Fund, has so far paid over $260,000 in claims against Biss.

Biss’s fleecing of small-time clients, whom he then ignored while he spent most of his time on Nunes’s lawsuits, raises a question that puts their campaign of lawfare in a new light. Maybe there was no secret donor financing the lawsuits. Maybe Biss was actually taking this money from people in Kentucky and Texas and using it to fund his real passion project: the ideological crusade against the press. Maybe he even thought he would be able to pay it all back when he won his big jury verdict against NBC or The Washington Post or Hearst and me. (For the record, there is no evidence that Nunes knew about the campaign of “dishonest conduct” by his longtime lawyer that’s been uncovered by the State of Vriginia.)

The last medical update for Biss that I could obtain was from last spring. His guardian reported that Biss had “made remarkable progress in his recovery,” and during a recent conversation, “was able to process and communicate about many concepts accurately.” Still, she said, his speech was like a “word salad” and there was “an element of cognitive impairment.” Biss was “still vulnerable to exploitation.”

In January 2025, the Eighth Circuit, in another opinion written by Colloton, affirmed the Iowa court’s decision in the lawsuit about the Nunes family dairy in Iowa. Nunes and his family declined to ask the full court for a rehearing. I thought perhaps they would try their luck with an appeal at the Supreme Court. But last night, April 28, at midnight, the deadline for that appeal expired, and the case is now officially over, more than six years after I wrote the original article.

Wow. Just wow. Better than episode of Dateline. Drives home the hard truth about some of the people who now hold a measure of power. Thanks so much for sharing that story, Ryan. Looking forward to your commentary on the current political climate. Much success with your new endeavor!

Great article! Just another example of how fraudulent litigators tied to the Trump regime are as incompetent as they are corrupt.